Theoretical Orientation

I believe the theoretical underpinnings of a skilled psychotherapist’s work should not be readily apparent to his or her clients. This is not because the therapist is hiding anything, but rather using jargon like ‘transference’ or ‘projection’ would not likely add much to the interaction, and may likely actually become an interference. That said, I have a psychodynamic background and I incorporate a number of different theories and areas of ‘knowledge’ to augment my understanding. I will describe each of these interests.

Psychodynamic Theory

Psychodynamic theory is a rich and evolving family of theories. One thing that all branches of psychodynamic theory hold in common is that early experiences are crucial. For example, the qualities of our early attachments has profound influence over how we experience and manage anxiety. Our sense of self develops in relationship to our parents or guardians, siblings, grandparents, other family members and important friends (or neighbors). These experiences can be modified (initially) by our own subjective interpretation of these events or relationships. For example, it is not uncommon for a child who was abused or neglected to attribute those experiences to his or her being a ‘bad’ child. If not checked, either by other experiences or by therapy, the person can continue to feel ‘bad’ or ‘unworthy.’ This could result in his or her not trusting others’ love for them, or perhaps even their own motivations – always second-guessing themselves.

No one sees the world with perfect accuracy. We all have our own subjective experiences of it. These experiences are, to varying degrees, influenced by our personal psychology. To the degree there is an issue that is unresolved, more of our experiences in the world (romantic relationships, work relationships, etc), tend to be organized along the lines of our preoccupations. A person whose parents were angry and volatile may always find they are anxious around their boss. Other authority figures may be experienced as being like the parents, even when evidence to the contrary is readily available. (And, yes, this is where terms like transference come in – although one may never hear it in therapy).

It is the therapist’s job to try to understand the various communications and to develop hypotheses with the client about his or her experience. The therapist helps the client become aware of motivations, thoughts and experiences which are normally outside of conscious experience.

Developmental Theories

There are predictable tasks and events in most of our lives. These events, our personal interpretation(s) of them and how our parents/guardians/families helped us through them can have a profound impact on our sense of self. For example, one’s jealousy over the birth of a sibling can be taken as a predictable experience with which the child will need some help or, perhaps, the child can be made to feel badly about him- or herself. The older sibling may not only feel displaced, but may feel he or she is a ‘bad’ child for his jealous feelings over the loss of some of the parents’ attention. At times, these problems can continue and impact peer relations, and perhaps even relationships with co-workers.

Our development does not stop in childhood or adolescence. While these are certainly formative times, there are continued developmental tasks and challenges to be faced throughout life. For most people, there is the task of finding an appropriate partner. Many times old issues play out with one’s significant other. There are the challenges of leaving home, becoming an adult or perhaps turning a certain age.

Many times reaching (or approaching) a milestone can be a time of stress. Significant milestones signal changes in our life and in the structures we have created for ourselves. For example, graduating from college means having to adapt to the next phase – trying to find a job, truly being self-sufficient, moving into the next phase of adulthood. Turning a certain age may have meaning to a person. Turning 40 or 50, for example may signal some foreclosure of opportunities, as well as some new opportunities. It is common for people, at these times, to re-examine (and re-evaluate) aspects of their past. “Did things turn out as I planned?” “I never did live in Europe/sky dive/finish my education/become a rock star.” The future has to be evaluated in light of the past, which dreams may still be attainable? Which may require re-thinking? Which may need to be grieved?

Sometimes we are ‘out of sync’ with our peers, or we are not where we ‘should be’ for our age or life stage. Sometimes a grandmother is not ready to become a grandmother and prefers to think of herself as a mother. Maybe we are not ready to leave our parents’ home. Or, even if we have technically left our parents’ home, we may treat our partner more like a parent than a partner, effectively keeping ourselves in the adolescent position. Sometimes we ‘remain behind’ because there were developmental tasks that we unfulfilled or because we were hoping for more (or a different ending, for example to our childhood, adolescence or early adulthood).

Historical Events

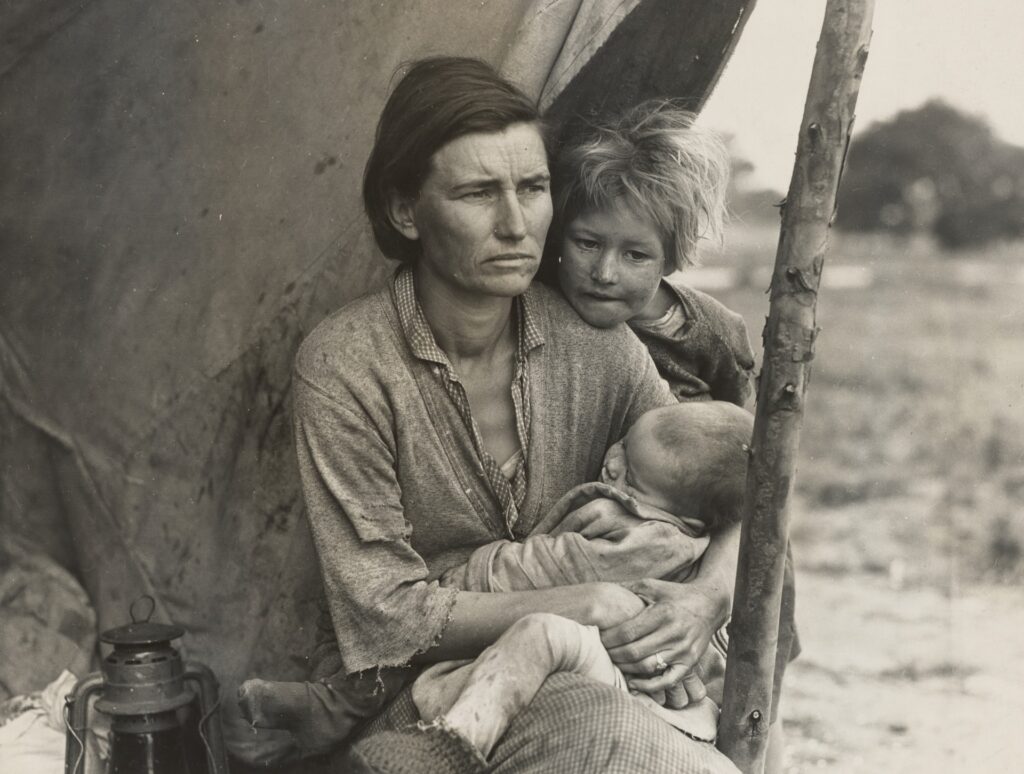

Various historical events – and even which age group we belong to at the time of those historic events can have significant impact on us. People who were children during the “Great Depression” may have particular issues about safety, about extravagance, or waste. Soldiers who have come back from any of our wars may be changed, and these changes can significantly impact their families and children. Children born now, will never know an America without a president who is not Euro-American. History shapes us, and we need to be aware of its’ impact.

Cultural Issues

There are many cultural and cross-cultural variables possible, I will only mention a few. Many of us come from families in which there was a recent immigration (within the past couple of generations). In these cases, we are all developing our own ‘amalgam’ of cultures. For example, some cultures expect that the child stays at home until they marry. Yet, in the dominant culture the explicit expectation is that the young adult move out to go to college, or essentially, as soon as possible. The person who has influences from both cultures could feel torn. He or she could feel embarrassed in light of the dominant culture. He or she could feel disloyal to his or her parents for wanting to move out.

Our sense of self, of family, of others and of our place in the world is heavily influenced by culture. People who come (or whose families have come) from a more collectivistic culture (where the emphasis is on the group and not the individual) may feel quite torn in the dominant culture – where the emphasis is heavily on “my happiness.”

Lastly, (for now) are the various impacts of immigration. Some families cannot emigrate together. Some family members get left behind, and have to wait. One’s sense of place in the world can be profoundly impacted by such events. “Why did they take my brother, but leave me with family?” Also, we have a myth that all people are happy/lucky to be here. While this may be true, in part, there are other truths as well. People who come to America often had little choice. These immigrants face enormous losses. They give up all that is familiar – friends, family, culture, familiar sites, customs, foods, smells and even the way the air feels.

Final Thoughts

Individual and familial developmental stages/tasks are different in different cultures (and even in various subcultures in our own society). We have to hold all these ideas as potentially important, and we need to understand that ideas can both inform and interfere with our understanding.

The therapist’s own maturity in understanding these points is important.

Thank you for reading so far.

Copyright © 2024 Scott Schulkin All Rights Reserved. Designed and Developed by MS Digital Agency